Sustainable infrastructure

Courtesy : www.nortonrosefulbright.com/

A staggering US$90 trillion is needed to finance infrastructure over the next 15 years. For the world to have a chance of meeting the targets set in the Paris Agreement following the global climate change negotiations in November 2015, the vast majority – if not all – of this infrastructure will need to be sustainable.

Whilst the scale of the investment needed is challenging, it presents a unique opportunity to build a sustainable future.

In this article Hannah Logan looks at the what, where, how and why of sustainable infrastructure and Joanne Emerson Taqi and Michael Weissman highlight some forward-thinking examples in the Middle East.

So what is sustainable infrastructure?

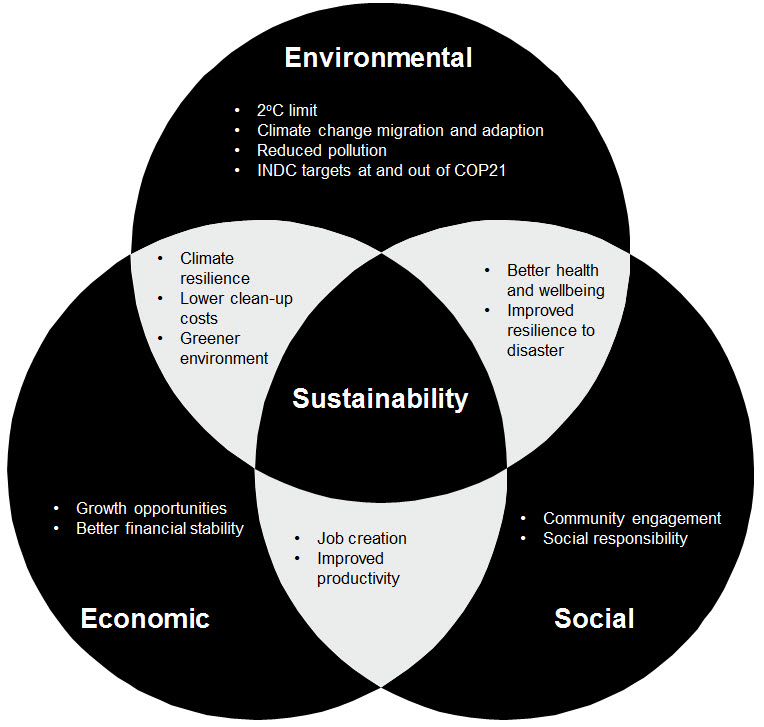

At its narrowest, sustainable infrastructure can refer to ‘green’ or ‘smart’ buildings. More broadly it can encompass a wide range of initiatives with a specific focus on energy, water and land management; green areas; smart technology and the use of sustainable, durable building materials. It can also refer to existing infrastructure which is retrofitted, rehabilitated, redesigned and reused. Whatever definition is used, sustainable infrastructure is generally considered to approach development from a holistic viewpoint and based on global and domestic sustainable development goals and durability and having regard to social, financial and political issues, public health and wellbeing, as well as economic and environmental concerns.

It is also about a step-change in public policy and private investment decisions so that climate resilience is an automatic and critical investment consideration for all sectors of the physical economy.

Key drivers

Sustainable infrastructure has overlapping benefits from physical, environmental, economic and social perspectives.

From a base environmental perspective, sustainable infrastructure aids climate resilience, which ultimately helps economic resilience. Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board, has spoken about climate change being a “tragedy of the horizon”, and highlighted physical risks to infrastructure that arise from the increased occurrence and strength of climate- and weather-related events, which could lead to un-insurability and resulting financial instability.

Sustainable infrastructure can also help countries meet their national targets as set in each country’s intended nationally determined contribution (or INDC) to the overall 2 º C goal set at Paris. According to the 2015 Synthesis Report on INDCs, infrastructure and sustainable transport are priority areas for many countries’ submissions.

From a wider perspective, sustainable infrastructure investment can be a source of economic growth, community wellbeing and financial returns.

Who and where?

There is an obvious focus on climate resilient infrastructure in countries most at risk from the physical effects of climate change. Low-lying countries such as the Maldives, the Netherlands and Singapore are all focusing on sustainable development to help mitigate the worst possible impact of climate change, including flooding and rising sea levels.

But the focus is both broader and deeper. National, regional and local governments, city mayors, town planning authorities, private investors and funders are all increasingly focusing on sustainable infrastructure investment.

Cities will be at the forefront of investment. By 2050, more than half of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas , bringing huge challenges – and opportunities – for investment in sustainable infrastructure across all sectors of the economy. Transport systems will need to be smarter, faster and more geared towards mass transit and electric vehicles. Buildings will need to be higher, greener and more energy efficient. Investment, and expertise, will be needed in urban planning, water and waste management, construction practices and materials, and sustainable energy provision.

Cities in emerging markets in particular have a unique opportunity to learn from the climate impact of cities in more developed jurisdictions and grow their economies and infrastructure along more sustainable lines. For example, Johannesburg has developed a forward thinking sustainable Spatial Development Framework integrating different stakeholder concerns to shape its urban planning in response to its forecasted growth from 4 to 6 million inhabitants by 2040 .

The private sector is also stepping up, with or without public sector assistance. Arup is designing car parks with built-in increased headroom in order to facilitate building use conversion in the expectation that the growth of smart electric vehicles, driverless cars and better mass transport will transform the ownership and use of cars in future. A leading Indian real estate developer is developing Palava, a greenfield smart sustainable city 25 miles outside of Mumbai, being built from scratch with 100% private funds. Start-ups and new apps such as Deliveroo, Uber Pool, Waze and a multitude of other innovations are helping to shape how we live in the cities of the future.

How can sustainable infrastructure be achieved?

What changes to law and policy will be needed and how could governments and policymakers ensure that sustainable infrastructure projects become reality? How could the finance gap, that is the gap between the sustainable infrastructure investment needed and current levels of investment, be closed?

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015 will help to put sustainability and resilience on the agenda for both new and ageing infrastructure. Overarching principles are filtering down from the international community to policy implementation at country, city and business levels.

Governing bodies at national, regional and city levels will be instrumental to the shaping of sustainable infrastructure goals and closing the finance gap in three key ways:

1. Policy measures

- Developing clear and supportive policy and regulatory frameworks and enabling environments to ensure sustainability and resilience become embedded in planning and investment criteria – both for public spending and as a signal for private investment.

- Observing INDC commitments by implementation of domestic legislation to make emission reductions and reporting mandatory.

- Including sustainability criteria in procurement processes and investment plans.

- Improving transparency, anti-corruption, service delivery and time and cost evaluation and management in the public sector.

2. Information flows

- Publishing long term infrastructure plans to help develop a clear pipeline of bankable projects for investors.

- Communicating the benefits of sustainable infrastructure.

- Working collaboratively with other governing bodies vertically and across jurisdictions to develop standards and collect performance data to improve project comparability, future proof investments and share information about successes and failures.

3. Mobilising finance

- Diverting fossil fuel subsidies to sustainable infrastructure development and putting a price on carbon. According to the OECD in 2015, an estimated US$160 to 200 billion per year is spent by OECD countries on fossil fuel subsidies. This is despite the G20 commitment in 2009 to phase out these subsidies. In the same year it was estimated that less than 15% of global carbon emissions are subject to a carbon price.

- Developing financial and tax incentives and financial support mechanisms.

- Leveraging public funding and credit enhancement mechanisms to attract private investment.

- Funding the upfront costs which make sustainable infrastructure projects initially more expensive than conventional projects.

- Boosting capital markets and developing standards for green bonds.

Both developed and emerging economies have already taken steps towards implementing these strategies. In the Middle East, for example, the Federal Government of the UAE has introduced a zero waste to landfill strategy for Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah due to the large proportion of recyclable materials in the UAE’s landfills and opened several new recycling centres in the UAE. As another example, the Dubai Municipality introduced ‘Green Buildings Specifications’ in 2011 which seek to manage resources in buildings and improve the welfare of buildings’ inhabitants. Moreover, Estidama (which means “sustainability” in Arabic) is an organic sustainability framework introduced by Abu Dhabi in 2009 and seeks to ensure that all new development in Abu Dhabi is undertaken in a sustainable manner.

Snapshot: Masdar City, United Arab Emirates

A well-known example of an ambitious live development with a bold vision for sustainable urban infrastructure is Masdar City in the UAE. The project is led by Abu Dhabi’s renewable energy company Masdar, a subsidiary of Mubadala Development Company. Masdar aims to follow a radical new approach to developing the cities of the future and has produced a ‘greenprint’ showcasing the three pillars of sustainability – social, economic and environmental.

The sustainable infrastructure includes a combination of ancient Arabic architectural techniques and modern building technologies. Design for cooling and the use of prevailing winds are key features. The scheme includes smart shading by high performance façades, narrow streets for shade and wind channelling and site orientation to hone the capture of solar radiation, as well as a solar photovoltaic power plant with an installed capacity of 10 MW peak.

Planned transport infrastructure includes various low carbon systems: a metro line, light rail, cycle routes and a public electric bus network. International air traffic would be served by the adjacent Abu Dhabi International Airport. In common with other planned city projects such as the King Abdullah Economic City in Saudi Arabia, the focus is on walking, cycling and public transport. A planned ‘podcar’ personal rapid transit system reached pilot stage, though whether this will be developed remains to be seen.

Masdar is also seeking to move away from the traditional ‘take-make-use-dispose’ model and towards reusing and repurposing waste. In keeping with the strategy of diverting waste from landfill, the project utilises waste reduction measures and reuse of waste (including construction waste) wherever possible and recycling, composting and waste to energy schemes are envisaged. New methods of water management are also being explored to help manage the water balance in a sustainable way, such as reuse of wastewater for irrigation, more efficient sprinkling and landscaping systems, smart consumption arrangements and hot water provision via thermal receptors.