Courtesy : www.politico.eu/

Green deal

Don’t worry, it’s not a heavy read. The European Green Deal is a document so thin you could print it out and not feel like you would be in breach of an EU forestry directive.

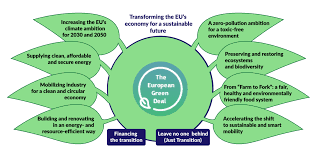

But that slim size conceals a big punch. Those 24 pages lay out a radical project to make the EU climate neutral by 2050 — that means the world’s second-largest economy will stop adding to the earth’s stock of greenhouse gases by then. It covers every aspect of society and the economy and includes goals for biodiversity and agriculture.

Why does this even exist?

It’s a sign that concern over climate change has migrated from the margins to the heart of EU policymaking. That’s a huge success for the scientists, lobbyists and campaigners who have waged a decades-long battle to make global warming a central concern — something helped by Australian, Siberian, Brazilian, Portuguese and Californian wildfires, melting icecaps, summer heatwaves, ferocious storms, coastal floods and steadily climbing atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

One can be a cynic about politicians and expediency, but in this case, the shift in perceptions is real. Policymakers are also being pushed by increasingly vocal protesters and a growing awareness that the time to cut greenhouse gas emissions is running very short.

Added to those environmental concerns, the EU is worried about being left behind in a green technology shift. China swallowed up the solar power industry, is way ahead in electric vehicles and poses a threat in wind power.

Finally, the EU sees climate change as an issue that allows it to play the role of a global power — pestering the U.S. to rejoin the Paris Agreement, making deals with China and pressing other countries to also boost their climate pledges.

Is it law yet?

The Green Deal isn’t a law. But it will inspire a legislative firestorm.

The centerpiece is the European Climate Law, which is in the final stages of negotiation between EU institutions. That will enshrine the goal to reach net zero emissions in 2050 into law, plus a host of measures to achieve it. EU leaders are aiming to agree major details in December, with the law to be finalized in 2021.

Beyond that, expect the coming year to see a flurry of new regulations, plans and changes to EU law: strategies for agriculture, hydrogen, building renovation, offshore wind energy, methane pollution, sustainable investment, the circular economy and a litany of others are all working their way through the Brussels bureaucracy.

As these come into effect, pressure will be on the 27 member countries to actually bring those new rules to life. That’s causing anxiety in coal-dependent economies like Poland, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria, as well as in capitals around Europe, which will need to start addressing emissions in tough places like their building stock, trucks fleets and steel plants.

What are the three big things to know?

Timmermans is sure to tell you that the deal is intended to be Europe’s “new growth strategy.”

But it’s about more than that. It’s a grand (or grandiose) vision for what Timmermans’ boss European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen calls an economy and politics “that is more caring.”

Success would result in a Europe that has been “tailored and re-engineered in a way that it that keeps you safe,” says Johanna Lehne, a policy adviser at the E3G think tank. “If you’re looking at a household in 2050, you have a completely transformed set of ways that you cook, heat your home, interact with other human beings, move around and the jobs you do.”

Finally, you need to know that both of Timmermans’ grandfathers were coal miners. So when he says there needs to be a “just transition, or there will just be no transition” (and he will), it’s because it’s close to his heart. Providing communities that are built on carbon-spewing industries with meaningful, dignified alternatives is one of the toughest — and most expensive — challenges the deal will face.

How much is it going to cost?

Upfront investments will be needed to switch energy, industry and transport to clean tech. Meeting Timmermans’ proposed 2030 stepping stone on the way to 2050 — a 55 percent cut in emissions compared to 1990 levels — will require an additional €82 billion to €147 billion in spending every year. That’s about half a percentage point of the EU’s GDP. Beyond 2030, the additional investments are 1 percent to 2 percent of GDP, about €4.6 trillion between 2031 and 2050.

Good investments pay themselves back, so the Commission predicts overall impact on GDP will be minimal. Also, none of this factors in the economic costs of inaction of climate change, which are devastating. Sea level rise alone could be costing Europe €135 billion to €145 billion per year by the 2050s, rising to €450 billion to €650 billion by the 2080s.

What are the biggest political problems?

Where to start? The political fight over the climate targets is about to enter a new phase. Next year, instead of arguing over whether the EU should cut emissions by 55 percent, countries will fight over who must shoulder the most burden.

Poorer Central European countries will say that the transition is more expensive or disruptive for them. They will argue that richer countries, with less carbon-intensive economies, should do more. The wrangling will start when Timmermans presents legislation on how to meet the 2030 target in June 2021.

The controversy will extend way beyond climate targets. How is Timmermans going to reform Europe’s existing policy infrastructure to ensure it all serves the emissions goals? He’ll have to find a way to get the auto industry to institute radical new emissions standards for cars and trucks, and accept that they will soon be subject to Europe’s carbon pricing system.

It might be best to avoid the subject of agriculture altogether. The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) — its largest subsidy program — and the Green Deal have some big issues to resolve if they are to work in alignment. The CAP is built on principles, such as maximizing productivity, which may conflict with green goals to use more land for burying carbon.

The distribution of the €17.5 billion Just Transition Fund will also be deeply contested. Under a European Council proposal, Germany, with its large coal industry, was slated to receive the second-largest share of the pie, despite being one of the bloc’s wealthiest countries. The European Parliament has called for the entire fund to be boosted to at least €25 billion.

What should I know that would surprise Timmermans?

Despite this being the EU’s most vaunted policy, it’s curiously lacking in detail. To understand why, it’s worth learning a bit about the U.S. program from which the Green Deal gets its name.

about:blank

When presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt promised a “New Deal” for a depression-struck U.S. in 1932, he didn’t really have a plan. It took time to develop the right tools to rebuild the economy. Once elected, he canvassed and experimented widely and brought in surprising thinkers and ideas.

The modern European version is just a year old and still in its early stages. It’s a 30-year project. The goal is clear, even if the man in charge doesn’t know exactly how it can be reached.

The ‘accidental’ adviser

The most important voice in climate change you’ve never heard of

By KALINA OROSCHAKOFF

Had Corinne Le Quéré been a bit more organized as a teenager, it’s likely she never would have become one of the most influential voices in the fight against climate change.

A prize-winning climate scientist, she’s an adviser on climate policy to both the French and British governments. Le Quéré chairs France’s High Council on Climate and is a member of the U.K. Committee on Climate Change — both independent scientific advisory bodies set up to keep government climate policy on track.

Her first calling? Sports.

Le Quéré, 54, wanted to be a sports teacher but missed the application deadline by a day … and ended up studying physics and oceanography in her native Canada.

Becoming a scientist happened “accidentally,” she said. “I didn’t know what to do. There is no scientist in my family; I didn’t know this existed as a profession … I went to science because I had a good physics teacher in high school.”

She “drifted” into oceanography “just because it was interesting. It attracted my attention,” she said.

That inadvertent shift in her career has had an impact on global climate policy. For many years, Le Quéré was the lead author of the Global Carbon Budget, a report by a group of scientists that looks at the latest state of research on the carbon budget and sources of emissions.

Timed to come out during the annual global COP climate talks, the report has often informed the agenda in the battle against global warming.