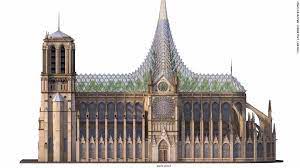

Courtesy : www.traditionalbuilding.com

Green classical architecture

Traditional practices have always been used to build the places where people go about their activities. Their value resides in their offering continuity and identity with a place. But a century or more ago traditional buildings began to be labeled as old fashioned by elites within the culture who wanted to replace tradition with Modernism that they envisaged building a future.

In recent weeks Modernism’s dominance in public, federal buildings were assaulted by those who would restore a role for traditional classicism. The Modernist establishment immediately counterattacked: the classicists want to institute an official style; they want to set back progress; worse, they want to restrict the architect’s right of personal artistic expression.

These attacks come from the legacy of the French Revolution. It spawned Marx, Lenin, and Mao but it gained only weak footholds among Americans. It did finally find sponsors among public housing officials, commercial developers, and cultural institutions, and after the Depression and World War II they seized the day and an American industry that had been converted to be the arsenal of democracy and put it to work building a Modernism devoted to freedom and economic prosperity. Glass-shrouded commercial structures sprang up in central cities, and shopping malls proliferated on the periphery while new, larger economic resources pushed monoculture suburbs across a landscape covered with traditional, tract-built houses along dead-worm and loop-and-lollypop pathways.

We now have two kinds of urbanism. One is Modernist, and it is intent on banning tradition and is out of sync with the other, which is a compromised version of the traditional towns and neighborhoods where American families want to live. The roots of this shriveled suburban landscape are in the colonial revolt that reformed the British legacy of the classical tradition melded with English common law that Americans then amended with the then-radical programs of political equality including equal justice under the law. This is the American version of the classical political and architectural tradition, which we need to recover and bring up to date. Modernism cannot do that.

The classical tradition takes its name from the ancient Romans’ arrangement of citizens into several classes for performing their social and military roles. The counterpart of these classes was in the distinctions between the buildings that served the purpose of the religious-civil life. These, too, were classified into a gradation from the every-day vernacular for dwelling, making, and trading to the highest and best for religion and the law, the ones we call classical. This gradation among classes of buildings allows us to know what the Greeks revered, about the range of civil and religious institutions in ancient Rome, and about the role of the Church in the lives of Catholics displayed in modern Rome’s urbanism while in the capital city of our self-governing democratic republic we see the supremacy of our three fundamental institutions, the Capitol, the White House, and the Supreme Court. The traditions of the art of building at work in these cities produced continuity across the gradations with the buildings serving the higher purposes earning the best materials, craftsmanship, and design. This same pattern can be seen in every city, town, village, and rural countryside not yet spoiled by Modernism.

Traditional classicism guided the design of the federal government’s buildings until the sponsors of progressive social programs sought to identify them with Modernist architecture. In 1962 a document titled “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture” began being circulated. It lacked any official sanction, but it gradually became de facto official policy, and in 1994 the GSA, the national government’s builder, initiated the “Design Excellence Program” that explicitly stated that the 1962 document was its “cornerstone:” its “principles are both the standard to which we must elevate our efforts and the yardstick by which we must evaluate our work.” (Italics added here and elsewhere.)

To pass muster the “style and form” of a building “must provide visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American Government.” It “must flow from the architectural profession to the Government.” And it “should … embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought.” Note that contemporary means not traditional. “The belief that good design is optional … does not bear scrutiny, and in fact invites the least efficient use of public money.”

The public money that is to be efficiently used comes from taxes. Taxes are collected on the basis of well-reasoned laws, and these must be based on principles, so what principles support the reason for spending public money for the buildings these documents seek? Certainly one reason is a preference among architects and their patrons for Modernist designs, but while an adequate reason for a preference can be “I just like it,” or “I sincerely believe this is right,” these are not reasons stemming from principles. Principles are comprehensive and fundamental laws, doctrines, or assumptions that bind a people into a civil order, and ours refer to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” and truths that are held to be “self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” This constitutional order is economically rendered in the lintel inscription of the 1830 Palmyra County Court House in Virginia: “The maxim held sacred by all free people: obey the laws,” where it is understood that, as Lincoln would later say, the laws are made by a government that is “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

The documents also accept the idea that “the development of an official style must be avoided.” Instead, proposals “must flow from the architectural profession to the Government” to ward off meddling by nonprofessionals that would comprise the free expression of the architects. Furthermore, without this provision governments might be inclined to sponsor the traditional classicism that carried the whiffs of Hitler’s totalitarianism even though it had been used for filling out the 1902 program for Washington that FDR had carried to near completion.

In referring to an official style the documents go off the rails. It accepts style as a worthy designation for a building’s appearance. The term is in common use, but it carries with it a chronological narrative for the history of art that was developed in the nineteenth century. That history divides the past into eras and credit each with its style: two phases of the classical styles separated by the Gothic, each with multiple subdivisions. In the decades around 1900 the modern era was hitched onto the sequence, and it called for its own, distinctive style, which became Modernism with its subsequent manifold stylistic variations. This prohibition of an official style was surely aimed at what by then was the classical as a style.

A sequence of styles stresses changes in buildings’ formal appearances across time while tradition, in contrast, fosters continuity. In the classical tradition, or classicism, changes in appearance provide means of distinguishing the status of a building’s purpose within the spectrum of purposes serving the entities of a civil or religious order. That spectrum runs in steps from homes sheltering and nurturing families to the buildings where the work of the authoritative institutions is done within civic subdivisions with the nation occupying the summit. Within the spectrum differences of time and place produce differences in appearance, and these are more conspicuous the higher the building’s status is. This was the way the history of architecture was understood before it was converted into a narrative of changing styles.

That earlier understanding in which classicism and the classical is not a style connects the principles of architecture that seek the beautiful with the principles of governing that seek the good or justice. This role of architecture’s service to the highest good is conveyed by the name classical or classic, a word used to describe excellence in any category from a faux pas to a vintage auto. To call a building or an architecture or an urbanism classic or classical is to connect its aspiration for beauty with the justice sought by the civil order that builds it and that it serves.

It is notable that beauty finds no place in the 1962 guidelines or in the 1994 reaffirmation. From the earliest articulations of the classical tradition justice and beauty have had a reciprocal relationship, and it is a given in the classical tradition that our human nature is equipped with the capacity to know justice and beauty when we experience and encounter them. On that basis we impanel a jury of individuals with no previous involvement in the case to hear evidence and render the verdict. And on that basis architects have always worked with the understanding that their work will be acceptable to the public at large.

The 1962 guidelines put no such trust in “We the People.” They declare that proposed designs for federal buildings “must flow from the architectural profession to the Government.” This distrust is part of Modernism’s substitution of judgments of taste for assessments of beauty and puts those judgments in the eye of the beholder where they are impervious to contradiction or gainsaying. This reduces them to personal preference that defy arguments based on principles. But beauty of things that we make gives body to enduring and universal principles accessible through reasoning and that guides the practices of the arts of building and of architecture just as principles provide the basis for justice in acts of governing. The practices in these two fields, but not the principals, have been constantly altered over time to account for new insights and changed circumstances, and these have been absorbed into the traditions that guide those practices. Our principles for the art of governing are articulated in our revered documents, and the practices have provoked lively interchanges and even a Civil War as “We the People” continue to achieve and practice their ideals. And so too in the arts of building and architecture, which are communal activities and are not the isolated province of individuals expressing their individual, personal beliefs about architecture by buildings for public purposes and using public money to build on public land. In replacing principles with preferences the guidelines reject any role for “We the People” to exercise ultimate authority over what is built even though we must pay for it and cannot avoid encountering it.

The principles governing the classical in architecture have a long history of using practices that have constantly absorbed new insights and innovations well into the twentieth century. The roots of those changes are in the principles articulated in the treatise that Vitruvius presented to the emperor Augustus. He put them into three groups of three each, but the substance is in two groups that have had a continuous history and enrichment ever since.

Every architect and many others know the first group’s trilogy: firmness, commodity, and delight. For firmness a building must endure across the time it is to serve its particular role; legislative buildings ought to outlast a circus tent. Commodity covers functions and edges itself into the 1962 document, but greatly defanged: “federal office buildings … must provide efficient and economical facilities,” but so must commercial office buildings, as if there is no difference between functions serving the gathering of wealth and those necessary to protect justice. Third, it must offer delight in those who encounter it.

This familiar trilogy can produce a building, but to produce architecture the building must satisfy the second trilogy as well. Less familiar because it rests on principles that have not been very interesting to architects in the age of Modernism in architecture, they are the imperatives of satisfying symmetria, eurhythmia, and decor. Symmetria and eurhythmia are different qualities of the same thing, which is the building’s reproduction or imitation of the order, harmony, and proportionality of nature (in the classical, not in the romantic, sense) using traditional compositions and a conventional apparatus of forms that are composed to produce a similitude of nature’s qualities.

Symmetria is much more than bilateral symmetry about an axis, which is not always present in a classical building. The term refers to proportionality, a principle that connects a building and its purposes to the order, harmony, and proportionality of nature and of a means to its end. It is also present in a series of numerical ratios; in geometric figures that embody those ratios; in the relationships between number series; in the geometric ordering of living things, the human person foremost among them; and so on. It encompasses the fit between the component parts of a thing, be it a healthy meal, a prized horse, a loved house, or most especially a public building. And it pertains to that building’s place among others in urbanism where it addresses the relationships between the solids and voids, buildings and the open areas, and buildings and other material elements composing the places its builders live, and the relative importance of their purposes.

Eurhythmia is simpler. It requires that the architect make adjustments to the qualities of different materials and to the apparatus of components and their assembly that allows the building’s symmetria to be clear and unambiguous in its urban or rural setting. The simplest example: fatten a temple’s corner columns so that the bright light enveloping them does not make them look disproportionately small.

Finally decor (decorum; appropriateness). It means quite simply that the building’s site and appearance must express the relative dignity of its purpose in serving the ends of the civil order. The authoritative civil order commands decor (unless it gives the public realm away to private interests and personal self-expression). While traditions of the art of building produce a building that is a component of urbanism, the building’s final form responds to decor’s imperative to serve and express the purpose that its use contributes to the common good. In other words, decor polices urbanism to assure that it is a place where individuals can pursue their happiness and government can do its work of protecting and facilitating their natural right to do so.

The principles and practices establish reciprocity between the art of building and the art of governing within their shared origins in nature, that is, in natural law, or what Jefferson referred to as “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” The qualities of order, harmony, and proportionality as embodied in different traditions and times have bound people into societies or polities where the art of governing seeks justice. The tasks of governing are conventionally divided into four purposes: legislating, executing, judging, and defending the homeland. In our civil order we distribute this group into entities ranging from individuals up through families, neighborhoods, regions, counties, cities and states with the nation as the final arbiter and authority. Each of these possesses valued traditions that deepen and enrich the present with references to the past and suggest a secure future. And so too in the art of building, which supplies places for individuals to pursue their happiness.

When the traditions of a place are honored the architect makes traditional buildings and their service to society makes architecture where beauty is congruent with justice. Beauty is a powerful instrument for winning favor for the exercise of authority, but the beauty arises from the canons of beauty that satisfy the six principles from firmness to decor that apply to architecture with decor holding the ultimate authority no matter the quality or the ends of the authority the buildings serve. When the visual properties of a building seems out of kilter with the relative dignity of the role it plays we call it pretentions if it is at the lower end of the spectrum or gross, out of place, inappropriate, strange, bizarre, etc., at the other.

The congruence of beauty and justice has not enjoyed an eternal, unbreakable embrace in its career across history. The canons for assessing the achievements of each art are not transferrable from the one to the other. Beautiful buildings have and do serve disreputable and even evil purposes, and evil purposes have worn the mask of beauty to obscure their evil intent. This separability allows beautiful buildings and cities to offer happiness to people who would not have wanted to have lived in Renaissance Rome or late medieval Bruges. The presence of slavery until well into the modern world did not forbid the use of the classical tradition for the buildings that were built in America after the Civil War. And the fronts of pagan temples and domes symbolizing Christian beliefs could, and have, become part of the American republic’s urban furniture. The classical is not a time-bound style but an architecture founded in and arising from enduring and universal principles, and that makes it an architecture that serves and expresses our novus ordo seclorum, which is perhaps the finest flower of the classical tradition.