Green affordable housing

Courtesy : www.smartcitiesdive.com/

Before I tell you about three of these great new developments, let’s begin with some background: affordable housing is a subject dear to my heart. In fact, I was born into post-World War II public housing in Hickory, North Carolina, where I lived with my parents until they could afford a private (but still affordably priced) apartment, along with employment, in the nearby city of Asheville. I was well into my twenties before I experienced any way of living, really, other than “affordable housing.” That said, I should stress that in our case affordable meant small but it did not mean unpleasant; I have a lot of happy memories from those days.

Indeed, even with respect to public housing I tend to think that the authors of government programs have tried to do their best for their clientele. But budgets have been tight, and some well-meaning concepts have not stood the test of time. Subsidized housing hasn’t been a failure, in my opinion – millions of Americans have enjoyed decent lives because of it – but it hasn’t been a universally rousing success, either.

In particular, great design – to say nothing of great green design – has not frequently been a feature of affordably priced developments. Writing a few years ago in what is now known as CityLab, Allison Arieff unsparingly criticized the dreary approach frequently associated with public housing:

“This soul-sapping approach to aesthetics is par for the course for affordable housing, which is meant not only to look low-budget but also low-effort. Conventional thinking on affordability proceeds from the misguided premise that anything well-designed will be, and look, expensive so it follows that design should not be a priority. Further, the argument goes, anything well-designed will be too appealing to eligible tenants, thus discouraging them from ever leaving. So affordable housing should not only be cheap, it should look cheap. As a result, much affordable housing is more punitive than homey, by design.”

That’s a brutal assessment. While I tend to think substandard design in affordable housing has come about more by inattention and a mass-production approach than by intent, there is little doubt that the results have often been lacking. Even worse, the effects of substandard design are frequently compounded by substandard maintenance over time, creating a “wrong part of town” even if things didn’t start out that way.

We need new models, and we need them fast. We especially need them in distressed neighborhoods to catalyze green, inclusive revitalization. Fortunately, I’m here to report that they are indeed on their way. I have seen quite a few over the last decade, but none more aesthetically and environmentally impressive than these three.

The Rose, Minneapolis

Let’s start with a super-green apartment complex in Minneapolis. I first came across The Rose in an Urban Land Institute email several weeks ago and took notice right way because of a stunning rendering and the project’s ambitious aspiration of achieving recognition under the Living Building Challenge, the most demanding of the green building performance rating programs.

According to ULI’s case study, the project comprises 90 apartments in two buildings. Significantly, it does not consist solely of affordable units but, rather, is mixed-income: 47 of the apartments are offered at subsidized rates to qualified residents, and 43 are market-rate; the two categories are indistinguishable with regard to finishes and appearance. Of the subsidized units, seven are set aside for residents who have experienced long-term homelessness; 15 are “section 8” apartments where tenants pay 30 percent of monthly income for rent. (Section 8 of the federal Housing Act of 1937 authorizes a federal rental assistance program administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.)

The Rose’s affordable and market-rate homes are interspersed throughout the project, which also includes among its outdoor features a 5,000-square-foot community garden. Additional outdoor amenities for all residents include a courtyard with “a lawn, a play area, a play surface that meets Americans with Disabilities Act standards, a rain garden, a patio with grills, a fire pit, and seating.” Indoor features include a fitness center, a yoga studio, and resident lounges, with floor-to-ceiling glass to maximize light and views. The units all have porches and, in the case of ground-floor apartments, access from the sidewalk as well as from the courtyard.

Green performance of any development is highly related to its location, generally the more central with respect to the metropolitan region the better. The Rose does impressively well on this score, its 2.3-acre site situated in an older, transit-accessible neighborhood just south of downtown Minneapolis. Simply put, people who live there don’t have to drive very much. The wonderful Abogo calculator from the Center for Neighborhood Technology estimates that households in the development’s neighborhood, on average, would generate only about 45 percent of the carbon emissions from transportation typically generated by households in the Twin Cities region as a whole.

The project enjoys a Walk Score of 86 (“most errands can be accomplished on foot”), a Transit Score of 76 (“transit is convenient for most trips”) and a Bike Score of 96 (“flat as a pancake, excellent bike lanes”). I wish there weren’t freeways nearby, but one can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the very, very good.

The Rose is designed to be 75 percent more energy-efficient than required by regional industry standards. Solar thermal panels are arrayed on the south side of each building and provide 35 percent of hot water needs. All stormwater will be captured and treated on-site, and all landscaping irrigation will be provided by graywater collected in cisterns with a combined 500-cubic-feet capacity. There is much more detail about the project’s green features (as well as its financing) in ULI’s case study.

The Rose was developed jointly by Aeon, a “nonprofit developer, owner and manager of high-quality affordable apartments and townhomes which serve more than 4,500 people annually in the Twin Cities area,” and Hope Community, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit headquartered in The Rose’s neighborhood and whose mission is inclusive revitalization of distressed neighborhoods. The developers consciously undertook the project as a model that, while aspirational, would be built on a foundation of replicable components and processes that could be applied elsewhere. Meyer, Scherer & Rockcastle of Minneapolis provided the project’s architecture.

Paseo Verde, Philadelphia

I have a small connection to my second example: Several years ago, my employer (at the time) Natural Resources Defense Council partnered with the Local Initiatives Support Corporation and a number of local community development corporations to work on green neighborhood revitalization. We wanted to build on the investment we had made over more than a decade as a founding partner of both the GGBC green building rating system and one of its most exciting offshoots, GGBC for Neighborhood Development (which we had developed alongside the Global Green Building Council and the Congress for the New Urbanism). Our thinking was that the standards of GGBC-ND in particular could serve as guidelines for helping low-income communities and CDCs improve their own neighborhoods.

One of that revitalization program’s first undertakings was to advise the planning for a new affordable housing development in Philadelphia. The site was a bleak surface parking lot at the intersection of 9th and Berks Streets in a part of town that had suffered severe disinvestment over the years. But the location had some major assets, including an adjacent regional rail transit station and Temple University, just a couple of blocks to the west. It was the kind of urban neighborhood that, while perhaps not impressive at the time, was well situated to improve with the right kind of investment.

Little did we know then that Paseo Verde, as the new mixed-income development would be named, would become one of the greenest neighborhood-scaled developments in the US, earning platinum ratings from both GGBC-ND and GGBC for Homes.

An article posted on ULI’s Philadelphia blog site describes the transformation:

“Paseo Verde is a keystone development that connects an ethnically diverse, low-income neighborhood to the adjacent train station and to Temple University. Before the development, commuter trains hurried past a drab station and a dingy, fenced-in parking lot, shadowed by public housing on one side and blighted rowhouses on the other.

“Today, the same trains pull up alongside a mosaic of bright green panels, with tree-shaded roof gardens peeking through. A health clinic that had been hidden inside a public housing complex now announces its presence with a campanile, its wide windows facing a broad sidewalk bustling with pedestrians. Above are 120 environmentally sustainable homes–affordable for downtown commuters, university students, and families leaving public housing, all of whom enjoy green views and healthful amenities.”

As with The Rose, Paseo Verde is mixed-income: sixty-seven of those 120 units – all rental apartments – serve as market-rate housing while 53 are subsidized to be affordable to residents earning between 20 and 60 percent of the area median income. There is also a little more than 30,000 square feet of commercial space and a 994-square-feet community room.

Again, an appraisal of the development’s green features must start with its centrally located, highly transit-accessible and walkable site. Abogo estimates that households in the neighborhood generate, on average, only about 40 percent of the carbon emissions from transportation generated by households in the Philadelphia region as a whole. Paseo Verde’s Walk Score is 82; its Transit Score is 88; and its Bike Score is 72.

ULI’s case study on the development provides details on Paseo Verde’s many green features, and stresses that many of them double as amenities that help to market the project. Green infrastructure to control stormwater runoff, for example, includes “rain gardens, wide sidewalks with permeable paving, and green-roof courtyards that permit private decks for some apartments.” Indeed, the roofs are not only green in the sense that they are vegetated but also “blue,” collecting rainwater in specially designed fixtures that then release it gradually.

Energy efficiency measures include high-performance appliances within the individual homes (which are also individually metered) and rooftop solar panels that supply electricity to some of the development’s common areas. As in the case of The Rose in Minneapolis, great attention was paid to large windows to daylight both residences and common areas, providing tenants with views of green space and trees from every apartment and from the complex’s fitness room and inviting stairways.

Paseo Verde was developed by an equal partnership between the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha (Association of Puerto Ricans on the March), a Latino-based community development corporation with extensive experience in and a deep commitment to the project’s neighborhood, and Jonathan Rose Companies, a nationally known “mission-based, green real estate policy, development, project management and investment firm” headquartered in New York City. Architecture was provided by Wallace Roberts & Todd. In 2015 Paseo Verde was named project of the year by the Global Green Building Council’s GGBC for Homes program.

Via Verde, New York City

Finally, twenty years ago, or even ten years ago, one would have been hard pressed to name a more unlikely place for state-of-the-art green design than the south Bronx in New York City. Indeed, throughout the latter decades of the 20th century, the area stood as a national symbol of severe urban decay, best known for high rates of crime, gang-related drug violence, abandoned and decaying properties, and even an arson epidemic. It represented everything that had gone wrong in American cities.

But today the South Bronx is turning around, in some neighborhoods dramatically, and there is no better representative to illustrate that rebirth than what is probably so far the most celebrated of all US green affordable housing developments: Via Verde.

Via Verde has some elements in common with The Rose and Paseo Verde but is much denser, befitting its New York location. It provides 151 rental apartments affordable to qualifying low-income households and 71 co-op ownership units affordable to middle-income households, all on a 1.5-acre site. The ownership homes comprise a diversity of types including single-family townhomes, duplex units, and live-work units with a first floor work/office space. There is also some 9,500 square feet of retail and community space.

As with the Minneapolis and Philadelphia developments, Via Verde’s location alone supplies a great head start on green performance, but in the case of Via Verde the numbers are even more dramatic. In particular, the New York City region as a whole has relatively low carbon emissions per household for transportation, but households in Via Verde can expect to generate only 12.5 percent of that already-low regional average, according to the Abogo calculator. The project’s Walk Score is a striking 98 (“walker’s paradise”); its Transit Score is 97 (“world-class”); and its Bike Score is 72.

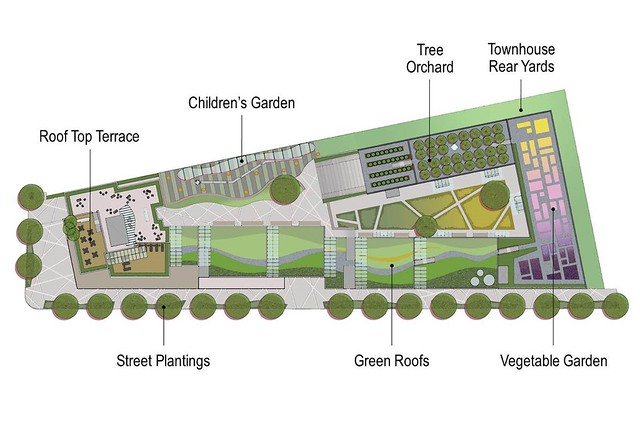

What makes Via Verde especially noteworthy, though, is that the architectural and development team has created a distinctively innovative approach to green and healthy urban living: this begins with a spectacular stepped architectural form that creates 40,000 square feet (roughly an acre) of resident-accessible green rooftop terraces at varying heights. Intended to integrate nature with the city, the rooftops provide functioning green infrastructure that can harvest rainwater, grow fruits and vegetables, and provide open space for residents. The garden level in particular is intended to provide both an organizing architectural element and “a spiritual identity for the community,” according to the Rose Companies’ web site. (Like Philadelphia’s Paseo Verde, Via Verde was developed by a partnership including Jonathan Rose Companies.)

Other amenities that contribute to the project’s theme of healthy living include open air courtyards; a health education and wellness facility operated by Montefiore Medical Center; a fitness center; and bicycle storage areas.

Beyond health benefits, Via Verde also exceeds GGBC Gold standards for building energy and performance. Along with the green roofs, which provide natural cooling in warm weather, the project utilizes low-tech strategies like cross ventilation, solar shading, and smart material choices, along with more tech-based strategies such as photovoltaic panels, high-efficiency mechanical systems, and energy-conserving appliances.

In one particularly innovative measure, the building’s design places some of the solar panels on the side of the building, not the roof as is customary; others are placed on canopies that provide shade for the garden areas. As a result, the roofs remain free for green space.

The project, which opened in 2012, was built by co-developers Phipps Houses and Jonathan Rose Companies, in partnership with Dattner Architects and Grimshaw Architects, pursuant to a commission won via the New Housing New York Legacy Competition. That competition was specifically intended to “re-engage design with the issue of affordable housing,” as former New York Housing Commissioner (and current federal budget director) Shaun Donovan told New York Times architectural critic Michael Kimmelman.

The importance of leadership projects

Returning to Allison Arieff’s point that affordable housing has been “meant not only to look low-budget but also low-effort,” these three projects suggest that there is indeed a better way, with housing designed from the start to be and look impressive, and to be and look impressively green. And, while all three might be described as leadership projects and thus somewhat atypical, the fact is that low-income housing is becoming better and greener right before our eyes, in part because of their examples (and the many additional examples being set by nationally-active investors such as Enterprise Green Communities and LISC’s Building Sustainable Communities program).

Indeed, I’ve been in this line of work long enough to spot an emerging trend when I see it. Is it too much to believe that the results so far portend well for what could become a new ethic in the way that we as a nation approach affordable housing? In his review of Via Verde, Kimmelman wrote eloquently about the importance of leadership projects:

“Higher costs for green construction have, over recent years, come to be accepted as investments in long-term savings. But spending extra for anything as intangible as elegance or architectural distinction? In Via Verde’s case maybe 5 percent more, by [Jonathan] Rose’s estimate, went into the project’s roof and its fine, multipanel, multicolor facade, with big windows, sunshades and balconies. What is the value of architectural distinction? How, morally speaking, can it be weighed against the need for homes?

“In terms of equitability and self-worth Via Verde does more than just aim to provide decent housing that fits noiselessly into its neighborhood. It aims to stand out, aesthetically, formally, as a foreground building, not another background one: to anchor the urban hodgepodge around it and make the area look more coherent, which in this case entails not echoing its context but redefining it. What is that worth? . . .

″[A]rchitecture doesn’t solve unemployment or poverty, and neighborhoods rise or fall as decent places to live on the quality of their background buildings, which do and should predominate. But they’re distinguished by their landmarks, by the buildings and places that people come to love.

“The greenest and most economical architecture is ultimately the architecture that is preserved because it’s cherished. Bad designs, demolished after 20 years, as so many ill-conceived housing projects have been, are the costliest propositions in the end.”

That is very good thinking and very good writing. I couldn’t agree more. All three of these projects give me hope, and not just for affordable housing.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.

Kaid Benfield writes about community, development, and the environment on Huffington Post and in other national media. Kaid’s latest book is People Habitat: 25 Ways to Think About Greener, Healthier Cities.

Related articles:

Smart City Technologies Fuel Urban Innovation

Discover why those cities that adopt an open source approach to smart city technology will be able to drive innovation and build holistic, interoperable systems that better serve their citizens.Download now

Get the free newsletter

Subscribe to Smart Cities Dive for top news, trends & analysisEmail:Sign up

MOST POPULAR

LIBRARY RESOURCES

COMPANY ANNOUNCEMENTS

WHAT WE’RE READING

PROPUBLICAIn Debate Over Chicago’s Speed Cameras, Concerns Over Safety, Racial Disparities Collide

THE ATLANTICCities Aren’t Built for

![]() SMART CITIES DIVE

SMART CITIES DIVE

Be the top smart cities leader in the room

Join the thousands of smart cities leaders who read Smart Cities Dive’s Daily Dive to stay on the pulse of the latest smart cities news and what it means for the industry.Get the Free Newsletter