Courtesy : permacultureapprentice.com

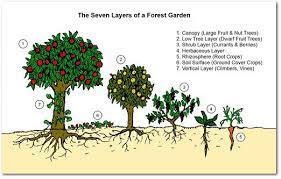

food forest

Then, looking down, I came across a small seedling sticking out the side of the wall, growing in nothing, with barely any soil between the stones.

Out of childish curiosity more than anything I decided to set it free from the heavy stones and leave it to grow on its own. That was 20 years ago…

Today, that seedling is this strapping young fellow on the image left – European Ash tree.

He has survived the droughts, heavy snows, pouring rains, and sub-zero temperatures all by himself, without anyone taking care of him.

As I sit under his shadow today and plan my food forest I’m curious to find out how trees flourish without human intervention.

How come wild apples, plums, and cherries from the nearby forest do so well while the cherry tree I planted in my orchard five years ago has died miserably? To understand this I needed to return to the place where the seed of this Mountain Ash tree came from and revisit my teacher – the forest itself.

Forests Are Our Teachers

Just by my house, some 50m away is an entrance to a forest. I visit there often, it makes me feel relaxed, I enjoy the serene sounds of nature, the falling leaves, birds, and other critters. Most importantly, I go there to observe and learn.

You see, given enough time every ecosystem ends up like a forest. This is the endpoint of ecological succession; a point where the ecosystem becomes stable or self-perpetuating as a climax community and, without any major disturbances, the forest will endure indefinitely.

This is exactly what you want your own food forest to be like. To achieve a low maintenance abundance of fruit, nuts, berries and herbs you’ll want to create a forest-like system where fertility comes from various sources, where you’re greatly aided by fungi, where wildlife is your primary pest control, where soil holds water like a sponge, and where you have a high diversity of plants.

You want a carefully designed and maintained ecosystem of useful plants and emulate conditions found in the forest.

However, the problem is often that you’ll find yourself starting out with a bare field, a blank canvas and the overall plan can feel a little overwhelming. Sometimes even reading books such as Edible Forest Gardens can make things harder rather than easier.

While creating my own food forest, I broke down the plan into smaller, manageable steps. I want to make as few mistakes as possible and to be honest, I don’t have time to make them.

So today I’ll let you in on my process and I’ll also share additional resources that will help you go from that bare field to a fully-functioning ecosystem inspired by forests.

Ok, let’s dive in!

1. What Do You Want From Your Food Forest?

First, you have to be clear about the ultimate goals of your project.

Why is this important?

You see, with a clear goal, everything becomes easier, you know where best to place your efforts and, most importantly, what are the priorities, what to focus on and what to postpone for the time being.

You have to think are you doing this because of: 1. being more self-reliant, 2. making an income, 3. producing healthy food 4. educating others 5. having a fun project for all the family

As you can see, each of these will require different considerations for your precious time and money. For example, if your goal is to create an income from your food forest, you’ll want to focus on researching which tree crops sell well locally and then think about how to grow them in the most efficient manner.

On the other hand, if you just want to be more self-reliant, you’ll want to think about how to create a diverse food forest with as many fruits, nuts and herbs as possible to fulfill your needs and stop being dependent on the grocery store.

Don’t overdo the thinking at the outset, but just be clear what you want from the beginning.

2. Explore, Sit Quietly and Observe, Analyse

–> Explore your local forest so you’ll have an idea what will grow best in your area

Start with taking casual walks in your local forest. When designing a food forest you want to learn from the local ecosystem and try to emulate it. This is why such observations are important, this is how you discover what plants will grow best in our area.

You’ll want to look around and identify the plants that are thriving. As Mark Shepard would say: identify the perennial plants, observe how they grow in relation to one another, and take a note of the species. Later on, you can use that list to find commercial productive variants of the wild plants that you can grow in your food forest.

This step is crucial, because if you want to create an edible landscape that requires less work and maintenance, you need to grow species that are well adapted to your area, i.e. species that are volunteering to grow around your site.

If you have nature as your ally and use the natural tendencies of the native vegetation, then you’ll be doing considerably less hard work. This is one of the fundamental permaculture principles of working with nature rather than against it.

For example, when I walked in my forest I saw elderberries, hazels, hawthorns, lindens, cherries, apples, junipers, and the list goes on. So, guess what I’ll be growing in my food forest?

I’d also be taking seeds from those naturalized species and using them as rootstock for my plants. But that’s a lesson in itself, so be sure to read my post on growing trees from seeds.

–> Sit quietly and observe your site

Next, sit at the future site of your food forest, no matter if it’s 5 or 50 min, just sit there quietly. Brew yourself some coffee or tea and just be mindful of what is happening around you. Immerse yourself and study the wildlife, feel the breeze, listen to the sounds of the natural world around you. You can learn a great deal simply by sitting quietly.

One of my best ideas, and one that saved me a lot of time, came when I just sat down and observed my site. For years, I tried to get a wild hedge under control and year after year I was cutting it, but it kept on re-sprouting. This mindless management involved a great deal of work, as I always found myself battling against the hedge’s natural inclinations.

It wasn’t until one day, when I was sitting quietly looking down at the hedge, that I came up with an easy solution to the problem. I asked myself a simple question: How can I let nature do the work for me? As I observed the hedge more thoughtfully, I realized that some of the species growing there were actually useful, while with others, I had even planned to grow them there anyway.

If I just gave a head start to species I want there, they would eventually overgrow the ‘non-useful’ ones, and I wouldn’t need to mindlessly cut down everything each year. Sometimes we are just too much in working mode to come up with solutions that are actually a whole lot easier. Having the time to observe, think and ask the right questions helps us save money, time and unnecessary labor.

These moments of mindfulness help put things into perspective and reveal a wealth of important information about the site itself.