COURTESY : www.npr.org

COMPOSTING

If you’re one of the millions of Americans now stuck at home because of the coronavirus, it might feel like you’re cooking more than you’ve ever cooked in your entire life.

And maybe, as much as you’re meal planning and reducing your food waste, there are certain things you’re just not going to eat. Like banana peels, or, if you’re me, a frightening amount of pineapple tops.

The good news? There’s a solution for your home food waste that doesn’t involve landfills: Composting! (Plus, keeping food out of landfills can help fight climate change.)

It doesn’t matter if you’re in a suburban home or in a tiny apartment. We’ll teach you how to turn your food waste into beautiful earthy compost in five simple steps.

Julia Simon for NPR

1. Select your food scraps.

Start with fruits and veggies — the skin of a sweet potato, the top of your strawberry. Also tea bags, coffee grounds, eggshells, old flowers — even human hair!

Meat and dairy products, though, are asking for trouble. Leonard Diggs is the director of operations at the Pie Ranch Farm in Pescadero, California. He says you gotta ask yourself, “Do you attract rodents? Do you attract animals to your pile? Meat products are likely to do that.”Sponsor Message

Other things that may attract pests? Cooked food, oily things, buttery things and bones.

Also important to note that some products say “compostable” on them — like “compostable bags” and “compostable wipes.” Those are compostable in industrial facilities, but they don’t really work for home composting.

2. Store those food scraps.

LIFE KIT

How To Reduce Food Waste

When you’re composting, your kitchen scraps should be part of a deliberate layering process to speed up decomposition. There’s a method for adding them to the pile (see step 4!), so you’ll need to store them in a container so you can add them bit by bit.

“It doesn’t have to be, you know, all the things that you find online that are really cute little ceramic containers,” says Diggs. He says it “can just be an old milk carton. When you make the first chop of the butt of that asparagus, boom, it could go right in there.”

Also, you can store the food scraps in a bag in your freezer or the back of the fridge. That’s an easy way to avoid odors and insects in your kitchen.

3. Choose a place to make your compost.

Worms Make Great Pets, And Other Reasons To Compost At Home

For this step, you gotta think about the space you’re currently living in. (I’m sure none of us have thought about this recently … Kidding!)

If you don’t have a backyard and still want a traditional composting experience you can take your food scraps to a compost pile that you share with neighbors or at a community garden.

(Of course, in the age of the coronavirus, make sure your community garden is open, and practice social distancing.)

If you want to break down your food scraps in your own apartment, there are still options. Jeffrey Neal, the head of the Loop Closing composting business in Washington, D.C., is a big fan of worms. He says you don’t need a big container for “vermicomposting” — a 5 gallon box will do. Or you can go bigger.

“There are times when I made [my worm box] an ottoman so I could relax with my feet up on them! You can use it like a piece of furniture.”

Another small space idea, Neal says, is fermenting your food scraps with a Japanese method called Bokashi. “All you need is a container you can seal and Bokashi mix, a colony of bacteria on grain.” (Here’s some more info on how to use worms and Bokashi.)

Of course, it’s totally fine if you want to give your food scraps to someone else to make compost. Some municipalities will pick up your food scraps from your home. You can also ask your local grocery stores, restaurants or farmers markets to see if they have programs to take food scraps.

If you do have some outdoor space, your compost bin doesn’t have to be complicated. “I think keeping it simple,” Diggs says. An old trash bin, an old wooden chest — just work with what you have available.

You can also buy a bin online or Digg says, “You could just create the pile naked!” Basically you can just have a heap of compost — but don’t put it up against a wall as it could stain it.

Julia Simon for NPR

4. Make the compost mix.

LIFE KIT

This Is A Good Time To Start A Garden. Here’s How

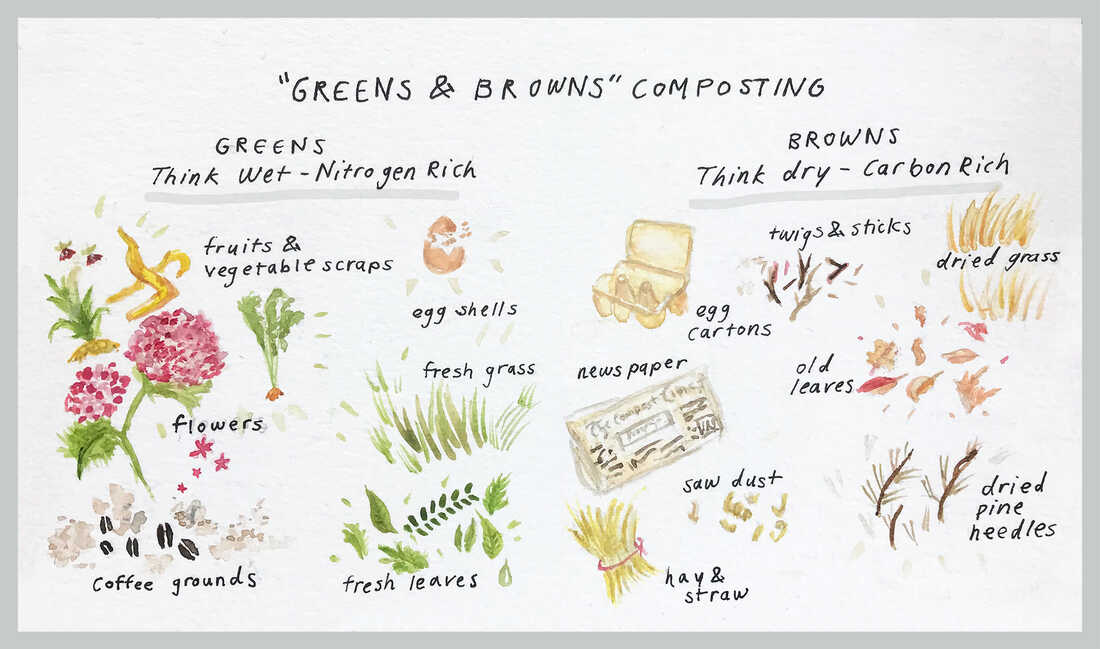

In the world of composting you’re inevitably gonna hear about “the greens and browns” — the two main ingredients for your mix.

“Greens” are typically food scraps, like fruit and vegetable peelings, coffee grounds, or, if you have a yard, grass clippings. These add nitrogen — a crucial element for microbial growth. Microorganisms are the true heroes of this process, they do the heavy lifting of decomposition.

“Browns” are more carbon rich — think egg cartons, newspapers, dried leaves, and pine needles. It helps to shred up the paper products before putting them in your pile.

A good thing to remember is that green materials are typically wet, and brown materials are typically dry. When you’re layering, you want the dry browns on the bottom with the wet greens on the top.

Diggs says the browns are key because they allow water to flow, and air to flow, something called aeration. That will make sure microorganisms can do their job. “If one hundred percent of it is water, then nothing is going on. The microorganisms can’t work. You got this soggy, smelly pile,” Diggs says, “So drainage makes a difference.”

A helpful analogy is to think of tending to your compost like tending a fire. Just as in a fire you need to structure the wood to get the air going, in compost you have to do a similar thing, adding spaces to give oxygen to those heroic microbes.

And it really is layering — browns then greens, browns then greens. The number of layers depends on your space and your amount of food scraps, but try to keep the layers to an inch or two. You can also put a little bit of browns on the very top to keep away flies and odors.

As for the ratio of “browns” to “greens,” you often hear three or four parts of browns to one part greens. Sometimes two to one. Ultimately you always want more browns than greens — again, gotta have the dry to sop up the wet.

5. Wait and Aerate

LIFE KIT

How To Talk To Kids About Climate Change

How long do you have to wait for decomposition? “If it’s hot, you could get there in two months pretty easy, ” Diggs says, “If it’s cold made, you could be there in six months. And for every component to break down, it might be a year.”

To keep things moving, you’ll want to turn or rotate the pile, perhaps with a stick or spade. Remember the fire analogy — you gotta make sure the air is flowing, that it’s wet but not too soggy.

As for how much you turn it, you’ll probably turn it less if you have the right ratio of greens to browns. Diggs says when you start out you might be turning the compost once every seven to 10 days.

Typically the more compost you have, the faster it will go.

Neal says in the end “the nose knows” when your compost is ready. “Bad compost smells, well, bad,” he says, “It’s like what a smelly trash can or dumpster smells like … Basically, it smells like a landfill.”

If it smells bad, it probably means it’s not decomposing — maybe your pile might be too wet or you might need to readjust your ratios of greens and browns.

Diggs says he loves smelling finished compost,”You know, it just smells so … Oh, gosh. Woody, earthy, but also a sweet smell. Or sometimes a sour smell. And the feel! How fluffy it is!”

When you’ve got that fluffy, earthy compost, put it in your garden, or in a plant on your windowsill. Or you can donate to your local community garden — just be sure to text ahead!

Of course composting takes patience — you might run into unexpected things. We don’t want you to give up so here are some more resources below.

Resources:

The Texas A&M AgriLife Extension has an excellent “compost trouble-shooting guide.” For example, it has suggestions of what to do if the pile has insects or is too wet.

- Jeffrey Neal from Loop Closing has compiled resources for those looking to try worm composting or Bokashi.

- Oregon State has a comprehensive guide for composting and “vermicomposting” — using a worm composter to break down organic materials.

- Cornell University’s Waste Management Institute has a more detailed guide to composting and “greens” and “browns,” plus a lot more resources on their website.